22 KiB

Securing Linux Containers

Maciej Lebiest, CY02

Informatyka 2st cyberbezpieczeństwo, niestacjonarnie

1. Table of contents

- Securing Linux Containers

2. Introduction

This document is a collection of simple, very generic tips and best practices related to security of Linux containers. Contenerization is considered safer by default, but then one can hear about discovered vulnerabilities that are primarly bad for applications in containers (Example: CVE-2023-49103). Tips and best practices collected here should help raise awarness about how to keep containers really secure. Contents are kept container-engine agnostic, but examples will be based on actual implementations (Podman, k8s).

3. Secrets

Secret is the most vulnerable data, as it usually can open access to other private data. They might also allow modification of the environment, which means possibilities for further access or many other forms of attack.

Warning

Don't use environment variables for secrets

Container isolation made providing and managing secrets somewhat harder, as they need to cross the additional barier. This casued the rather dangerous trend of providing secrets among many other configuration data in form of environment variables. At first sight it might look like good idea, but when actually compared to other means of storing secrets it turns out that environment variables might be much easier to access by attacker, than for example arbitrary files. CVE-2023-49103 is only an example of vulnerability which was considered to be more dangerous for contenerized apps, because of the vulnerability being based on gaining access to env variables.

3.1 Alternatives

3.1.1 Files

Files with secrets are common and broadly supported. With proper setup they can be also very secure.

- Keep configuration and secret files on entirely different path than other data

- If application runs main process under different user than worker processes (worker usually have direct contact with user interaction), the configuration should not be readable by the worker process user.

- Depending on the technology used, storage of the secret files inside of a container could be temporary/volatile. In kubernetes Secret objects are mounted as tmpfs. Example for mounting secret as tmpfs in pod:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: app

spec:

containers:

- name: app

image: registry.fedoraproject.org/fedora-minimal:latest

command: [ "sleep", "infinity" ]

volumeMounts:

- mountPath: /config

name: config

volumes:

- name: config

secret:

secretName: config

This produces readonly tmpfs mount inside:

bash-5.2# df -h /config/

Filesystem Size Used Avail Use% Mounted on

tmpfs 4.8G 4.0K 4.8G 1% /config

bash-5.2# ls -la /config/

total 0

drwxrwxrwt. 3 root root 100 Nov 9 14:00 .

drwxr-xr-x. 1 root root 24 Nov 9 14:00 ..

drwxr-xr-x. 2 root root 60 Nov 9 14:00 ..2024_11_09_14_00_47.4065932771

lrwxrwxrwx. 1 root root 32 Nov 9 14:00 ..data -> ..2024_11_09_14_00_47.4065932771

lrwxrwxrwx. 1 root root 18 Nov 9 14:00 secret.conf -> ..data/secret.conf

3.1.2 Secrets Management Services (kubernetes)

There are sophisticated tools for secret management and their deployment, available for kubernetes. For example HashiCorp Vault. It offers dynamic secrets, secret rotation, and access policies. Such tools are most helpfull in large environments and infrastructures, where secret management is split among many people.

4. Users and groups

Users and groups are standard mechanisms for security and permissions limiting in unix-like systems. Contenerization engines usually have possibility to arbitrarily assign them to the contenerized program process.

Note

Both user and group can always be specified by numeric id even if no actual user or group is assigned to them. When specifying with string name, the user or group must exist inside of the container (

/etc/passwd,/etc/group)

Note

Processes of rootless containers or containers with uid/gid mapping have different id's inside of container and outside. This can complicate things even more, but that also usually greatly increases security. In some scenarios such mapping can also cause trouble with files in container image, if their id's are out of mapping range.

Setting user and group

Containers have default user and group specified by Containerfile, but it can be changed when starting the container.

Containerfile/Dockerfile

In Containerfile the user/group assignment might take place many times in single build. Typical reason for that is to have high privilige (root) during build, and then set default to unpriviliged user at the end of build, so that containers will use it by default.

Setting just user to "user1"

USER user1

Setting both user and group

USER user1:group1

Setting just group

USER :group1

Changing user/group arbitrarily on container startup

Podman and Docker uses --user or shorter -u flag to specify both user and

group. The syntax is the same as shown for Containerfile. Example of

setting both user and group to bin, but user is specified with number ID:

❯ podman run --rm -it --user 1:bin registry.fedoraproject.org/fedora-minimal

bash-5.2$ whoami

bin

bash-5.2$ groups

bin

bash-5.2$ grep ^bin /etc/passwd

bin:x:1:1:bin:/bin:/usr/sbin/nologin

bash-5.2$ grep ^bin /etc/group

bin:x:1:

For Kubernetes, the user and group specification is located in pod definition:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

spec:

securityContext:

runAsUser: 1

runAsGroup: 1

Note

In kubernetes you can't specify user nor group using string name. Only numeric values are allowed.

Additional security

Linux kernel provides usefull feature - No New Privileges Flag. If set for process, it prevents the process from gaining more privileges than parent process. This effectively blocks use of capabilities, and setgid,setuid flags on files, which are known and powerfull tools for exploitation.

In Podman and Docker, the flag can be enabled using parameter --security-opt no-new-privileges

In Kubernetes, there is section related to security context per container:

(....)

containers:

- name: mycontainer

securityContext:

allowPrivilegeEscalation: false

(....)

5. Filesystem

By default the filesystem security of containers is quite good, specially when used with other mechanisms like selinux or mapped UIDs/GIDs, but it still have field for improvement.

Read-only

Both base filesystem and mounted volumes can be set to readonly. When using a read-only filesystem, certain directories may still need to be writable, such as /tmp or /var/tmp. This is where tmpfs (temporary filesystem) can be used. tmpfs filesystem mounts a temporary filesystem in memory, allowing these directories to be writable without compromising the overall read-only nature of the filesystem. The directory will be empty and will vanish on container shutdown which also increases security, if the temporary data is vulnerable.

Running Podman container with readonly base filesystem using --read-only:

podman run --rm -it --read-only registry.fedoraproject.org/fedora-minimal

Note

Podman simplifies use of --read-only by automatically creating read-write tmpfs mounts inside in places where it is usually needed, like

/dev/shm,/tmp,/run, etc...

Mounting tmpfs dir with specific size limit to Podman container using --tmpfs:

podman run --rm -it --read-only --tmpfs /tmp:rw,size=64m registry.fedoraproject.org/fedora-minimal

Mounting podman volume as read-only is done by specifying ro mount option

after : separator, for example --tmpfs /test:ro, -v /host/path:/container/path:ro

On Kubernetes to set base filesystem of a container to read-only, there is

readOnlyRootFilesystem: true attribute in container security context. To

mount any volume as read-only, there is attribute readOnly: true in mount

section.

Full kubernetes example of read-only base filesystem and example volume:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: readonly-pod

spec:

containers:

- name: mycontainer

image: registry.fedoraproject.org/fedora-minimal:latest

command: ["sleep", "infinity"]

securityContext:

readOnlyRootFilesystem: true

volumeMounts:

- mountPath: /test

readOnly: true

name: tmpfs

volumes:

- name: tmpfs

emptyDir:

medium: Memory

sizeLimit: 64Mi

Additional Protection with nosuid, noexec, and nodev

To further enhance security, you can use the nosuid, noexec, and nodev mount options for volumes. They can also be used for tmpfs mounts.

- nosuid: Prevents the execution of set-user-identifier or set-group-identifier programs.

- noexec: Prevents the execution of any binaries on the mounted filesystem.

- nodev: Prevents the use of device files on the mounted filesystem.

Example using Podman:

❯ podman run --rm -it --read-only --tmpfs /test:nodev,nosuid,noexec registry.fedoraproject.org/fedora-minimal

bash-5.2# mount | grep /test

tmpfs on /test type tmpfs (rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime,context="system_u:object_r:container_file_t:s0:c240,c646",uid=1000,gid=1000,inode64)

6. Resources limits

Setting resource limits for containers is required to ensure that no single container can consume excessive resources, which could impact the performance and stability of the entire system or neighbour systems.

CPU

Since there is no virtualization, the cpu is visible with all its cores and

threads inside of a container. Therefore cpu limiting is done by limiting

cpu time using scheduler. Usually the limitation unit is vCPU. In Podman

you can set the limit using --cpus flag. For example --cpus=2 will limit

cpu time to 2/X of total cpu time current host have. In case of cpu with 16

threads this means that container can use up to 12.5% of whole cpu power. This

does not mean assigning the cpu time to specific physical threads, therefore

high load in that container will be loadbalanced on all physical threads,

without allowing to utilize too much of time.

In case of Kubernetes this works the same, limits are specified per container:

(....)

spec:

containers:

- name: app

resources:

limits:

cpu: "2"

(....)

RAM

Limiting RAM for container looks similar to cpu limiting. Except that when software inside of a container tries to cross the limits, it will be handled more brutally - RAM hungry process will be killed. This might be not that intuitive for application, as here again the app sees all the memory available in host system, and it does not know about the limits (unless configured).

Podman have simple flag --memory which configures the limit. --memory=512MiB

will limit to 512MiB.

Kubernetes works similar:

(....)

spec:

containers:

- name: app

resources:

limits:

memory: "512Mi"

(....)

7. Network

For network isolation, Linux containers leverage network namespaces.

A network namespace is a feature provided by the Linux kernel that allows for the creation of isolated, independent network stacks. Each network namespace has its own separate set of network interfaces, routing tables, firewall rules, and other network-related resources. This gives complex possibilities for network configuration, but it stimulates differences between container engine implementations. Additionally rootless containers, which are considered safer, need to fallback to different network components, with reduced possibilities, as managing network is strictly root based.

Desktop tools

Container engines suitable for desktop like Podman usage usually have limited options for network configuration. They allow to isolate pods from host and each other with different network addresses pools, and even disabling the network at all, which is very safe, but very rare.

For such tools there could be few rules that should increase security:

- Don't disable isolation. Isolation makes access harder for remote attacker, even if he can access any port on the container host machine.

- When opening ports to access the app from outside, set binding to the least

accessible but sufficient interface/address. For example If you expect only

to access the app locally over localhost, you could bind to localhost in

Podman using flag:

-p 127.0.0.1:8080:8080to open the port 8080 only for localhost

Kubernetes

Kubernetes gives much greater possibilities for both ingress and egress. Primary tools for that are Network Polcicies, which are implemented via plugins (therefore they might be not available on some k8s clusters).

Network Policies allow for very accurate limitation of network traffic, thanks to their possibilities:

- Using labels to select the pods to which the network policy applies. This allows you to target specific groups of pods based on their labels.

- Applying network policies across namespaces by selecting namespaces based on their labels.

- Defining rules based on specific protocols (TCP, UDP) and ports to allow or deny traffic.

- Support for arbitrary CIDR-formatted network addresses ranges.

Example network policy definition:

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: NetworkPolicy

metadata:

name: example

spec:

podSelector:

matchLabels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: app1

policyTypes:

- Ingress

- Egress

ingress:

- from:

- namespaceSelector:

matchLabels:

kubernetes.io/metadata.name: app

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 123

- protocol: TCP

port: 456

- from:

- ipBlock:

cidr: 10.43.0.0/16

- ipBlock:

cidr: fe80::8cb6:aff8:8dc9:f511/64

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 443

egress:

- to:

- namespaceSelector:

matchLabels:

kubernetes.io/metadata.name: kube-system

ports:

- protocol: UDP

port: 53

- to:

- namespaceSelector:

matchLabels:

kubernetes.io/metadata.name: db

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 5432

8. OCI Images

Containers technically don't require images, the base filesystem can be provided in different way, but OCI images become standard in the industry. Images are another important element of (in)security in contenerization. It is crucial to understand basics of that format, as it can for example leak secrets to the public, if used incorrectly.

8.1 Building

It is obvious that one should not hardcode secrets into an image. Unfortunately less users is aware how not to do that. When building an image, any instruction that can modify filesystem of the built image, will be saved separately as a layer. By default each layer is kept in the image, even, when in the end all contents of some of those layers was removed.

Example of insecure Containerfile:

FROM registry.fedoraproject.org/fedora-minimal

# Copy secret into the image (bad practice)

COPY secret.txt ./secret.txt

# Use and delete secret (but it's still in a previous layer)

RUN cat secret.txt && rm secret.txt

There is a way to modify image-to-be filesystem in much more secure manner, which also brings other benefits. It is called multi-stage build and, as the name suggests, contains multiple stages, where only layers of the latest will be saved in the resulting image.

The Containerfile can look like that:

# Stage 1: Use secret during the build

FROM registry.fedoraproject.org/fedora-minimal AS builder

WORKDIR /app

# Copy application files

COPY app/ /app/

# Copy the secret into the build stage

COPY secret.txt /app/secret.txt

# Use the secret securely (e.g., configure app)

RUN cat /app/secret.txt && echo "Configuring app with secret" > config.txt

# Removing the secret in this example is needed, because in the next stage

# the /app dir will be copied as a whole

RUN rm /app/secret.txt

# Stage 2: Final image without secrets

FROM registry.fedoraproject.org/fedora-minimal

# Nothing is saved from previous stage

WORKDIR /app

# Copy only the necessary files from the builder stage

COPY --from=builder /app/ /app/

This approach also helps keeping the images minimal, without any other leftovers, which also can improve security.

8.2 Scanning

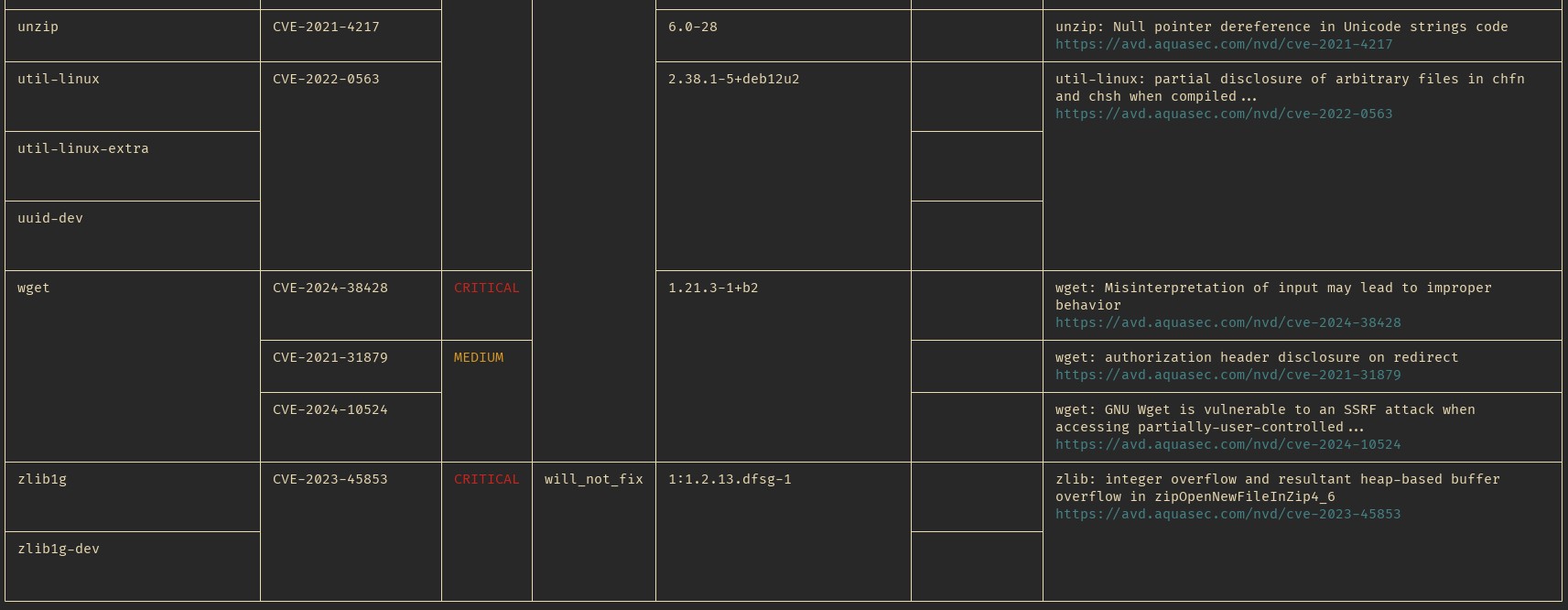

Images can be scanned for vulnerabilities. This is usefull for any type and source if images, since vulnerabilities appear even in the most basic components like language interpreters, libC libraries, etc. There are tools for manual scanning like trivy, and some registries like Harbor have builting optional automatic vulnerability scanning for any stored image.

These tools can provide descriptive analysis of image contents, taking into account versions of most software stored inside (if supported).

Example fragment of output of trivy scanning a python image:

9. Selinux

SELinux (Security-Enhanced Linux) is a security module for Linux that enforces mandatory access control (MAC) policies to restrict the actions of users and applications based on predefined rules, enhancing system security. SELinux works by labeling all files, processes, and resources on a system with security contexts. Policies define rules about how these labels can interact. When an action is attempted, SELinux checks the labels against the policies and either allows or denies the action based on the rules, enforcing least-privilege access.

This document is too short to explain in detail how selinux works, but for containers management most important concepts are MCS (Multi-Category Security) and MLS (Multi-Level Security), described in RedHat docs: link

Selinux additionally secures the contenerized program, not allowing to access resources from outside. Container engines like Podman randomize categories by default, so for example 2 different containers cannot access the same volume.

Proof of categories randomization by running subsequent containers and checking their selinux context:

❯ podman run --rm -it fedora-minimal cat /proc/self/attr/current

system_u:system_r:container_t:s0:c340,c364

~

❯ podman run --rm -it fedora-minimal cat /proc/self/attr/current

system_u:system_r:container_t:s0:c202,c993

~

❯ podman run --rm -it fedora-minimal cat /proc/self/attr/current

system_u:system_r:container_t:s0:c259,c971

If two or more containers have matching categories (sorted categories on the same position match or are not set), then such containers can access the same shared volumes.

For example (podman uses :Z flag on volume to propagate selinux context on all files inside):

First starting container with 2 categories:

podman run --rm -it -v ./test:/test:Z --security-opt label=level:s0:c222,c11 fedora-minimal

bash-5.2# ls -Z /test/

system_u:object_r:container_file_t:s0:c11,c222 test2

system_u:object_r:container_file_t:s0:c11,c222 test2.txt

system_u:object_r:container_file_t:s0:c11,c222 test3.txt

Then second container with a subset of categories in selinux level will change the labels, but still both containers have full access to the volume:

podman run --rm -it -v ./test:/test:Z --security-opt label=level:s0:c11 fedora-minimal

bash-5.2# ls -Z /test/

system_u:object_r:container_file_t:s0:c11 test2

system_u:object_r:container_file_t:s0:c11 test2.txt

system_u:object_r:container_file_t:s0:c11 test3.txt

Changing the level in second container to something like

label=level:s0:c11,c33 will prevent access for the first container.

For shared volumes container engines like Podman or Docker have flag :z,

which in contrast to :Z does not apply any categories, just plain level s0:

❯ podman run --rm -it -v ./test:/test:z fedora-minimal ls -Z /test

system_u:object_r:container_file_t:s0 test2

system_u:object_r:container_file_t:s0 test2.txt

system_u:object_r:container_file_t:s0 test3.txt

This allows any container with any categories potentially access this volume. And this is place for improvement - if the files inside of a volume are main protected resource, it would be safer to label it with categories. If there are multiple containers that need access to the volume, they just need to have matching categories. This somewhat reduces isolation between those containers in terms of other filesystems and other resources protected by selinux, but that usually will be not much of a problem, considering they use shared volume.

In kubernetes specifying labels happens for whole pod, which can have multiple containers:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

spec:

securityContext:

seLinuxOptions:

level: "s0:c12,c45"

(....)